Blog Stage 2

Looking Back on a Semester of Growth

ILA Analysis and Recommendations

Blog Stage 1

Blog Stage 2

Looking Back on a Semester of Growth

ILA Analysis and Recommendations

Blog Stage 1

At the conclusion of this semester, I could not be more pleased with what new revelations gave come to me through CLN650. I always knew Inquiry learning existed, but it was on the outer fringe of awareness and something only whispered about in schools. Sure, it sounded good- what little I knew and remembered from my 4 years at university. But still, there were 3 questions that burned in my mind. After 13 weeks of discovery, observation and many, many struggles, these questions awe now easily answered.

1/ Why are teachers so afraid to use this approach? What about it makes some of the hardiest teachers baulk at the thought and say “It’s just too difficult to make happen”.

It is not fear that has driven teachers that feel like this, but rather- apprehension. Wariness of the unknown. Inquiry learning is extensive and potentially complicated. If not planned and implemented properly, issues can arise and compromise the effectiveness of a task. For a inquiry unit to be carried out well, a number of factors come into play. Firstly, the amount of student-directed learning is beyond any other method of teaching. Therefore, students must be well aware of expectations; well versed in information literacy skills such as locating, evaluating and synthesising; and kept on task. If scaffolding and teacher observation does not take place, it becomes that much more difficult to achieve the intended outcomes.

2/ Which is more beneficial- Guided Inquiry (Kuhlthau) or guided inquiry (science)?

Both methods have their own merits and are used in different instances. ‘guided inquiry’ within science is an inquiry-based learning method that is appropriate to science in particular. Scientific inquiry is a complex, rigorous research process based on experimental methods. It involves the formation of a hypothesis (or research question); the planning and implementation of experiments; analysis of findings before presentation and construction of data and theories (Lupton, 2012). It can be seen as a process that is heavily reliant on scientific method in order to construct meaning. On the other hand, Kuhlthau has created her own version of Guided Inquiry that involves a questioning framework and student-directed learning. Rather than a scientific approach, this method focuses on the generation of questions from students, and intrinsic motivation to retrieve and make meaning from information. Depending on the discipline under question, each inquiry method has its own merits. For my ILA, Guided Inquiry (Kuhlthau, 2007) is most appropriate because, being a History unit, there would be no merit in using a scientific approach and experimentation to develop inquiry questions.

3/ Are there any templates and proformas that can be helpful to the creation of these units?

The best way to begin designing a Guided Inquiry unit is to use the Information Seeking Process framework as a basis for design. I did not come across any proformas during my learning journey, but I have found that, as my understanding of ISPs develops, it is far easier to develop units of work that incorporate elements of each ISP stage. As the range of learning areas is so vast, it would be very difficult to find a proforma or template fitting your exact needs. In the future, I would begin the creation of an inquiry unit by building a basic table with each ISP stage labelled separately, before filling in the blanks with unit information.

———————————————————————————————————————————-

The overall Blog Stage 2 Information Seeking Process

The chart below displays the events and stages that I followed along my learning journey, according to the stages of Kuhlthau’s Information Seeking Process.

I have found this unit to be one of the most valuable over the course of my Masters degree. Having had no experience of inquiry learning in the past, it was wonderful to have the opportunity to go into a secondary school and observe a History unit in action. Working with and learning from the class teacher has opened my eyes to the immense potential that Guided Inquiry has within education. I have a far greater understanding of information literacy and have developed a desire to push for its full integration into both library education and classroom learning.

Most of all, I have come to understand the need for change within the education system. For learning to be a transformative experience, students must be critically engaged in practice that is collaborative, student-directed and differentiated. “The basis of a transformative perspective is that to be literate is for individuals and groups to be empowered to challenge the status quo and to effect social change.” (Lupton & Bruce, 2010, p.5). Literacy soon becomes subjective, empowering and liberating. However, much work is needed to bring learning experiences to this point. We must engage students in experiences that are driven by their own inquisitive nature and desire to find answers. It is not enough to hope that students ‘pick up’ the information literacy skills needed to become active and questioning members of society. Rather, as teacher-librarians, it is our duty to teach and develop these skills through interdisciplinary, rich learning experiences that build critical, higher order and problem solving skills.

References

Lupton, M., & Bruce, C. (2010). Chapter 1 : windows on information literacy worlds : generic, situated and transformative perspectives, in Lloyd, A., & Talja, S., Practicing information literacy: bringing theories of learning, practice, and information literacy together. Wagga Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, 3-37.

Kuhlthau, C. (2007). Guided inquiry: Learning in the 21st century. Libraries Unlimited.

The purpose of this subject, Information Learning Nexus, was to delve into the world of inquiry learning, and develop new understandings and new experiences. Having no chance to teach a class of my own this year, I decided to spend some extra time at my placement secondary school with a teacher that was willing to let me shadow her and learn from her. With the unit being part of the subject of History, which has always been close to my heart, the chance to see how secondary history units are structured and implemented was an opportunity that could not be refused. My experience observing the teaching methodologies of another has helped me understand the need to involve students in all elements of the Information Seeking Process, and the potential pitfalls that may arise.

Australian Curriculum

As this unit of work was an Outcome, it had predetermined elements and achievement standards required by the Victorian Government and the Australian Curriculum. Because of these requirements, it made it very difficult to be flexible and provide students with the ownership and responsibility that are key characteristics of the Information Seeking Process. While students made their way through many of the ISP stages, there were elements missing that could have been utilised to promote a broader, more extensive learning experience with a greater number of information literacy skills involved. The ISP will be examined to determine the inquiry/information literacy model used and determine, to what extent this unit accurately demonstrates an inquiry based method of learning. The following image demonstrates the extent to which the Australian Curriculum standards for Unit 2 were achieved. Green indicates elements done well; yellow indicates a partial completion; and red indicates that the stage was not evident.

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority, Australian Curriculum, 2012

It can be seen that every single standard was achieved, at least to some degree. Whilst the majority of the unit was closely tied in with the Unit 2 standards, it should be noted that the inquiry portion was highlighted in yellow. This is because, while students could generate questions and sub-topics to some degree, the initial topic and tasks were nominated by the teacher. This does not allow for a full opportunity of students generating their own inquiries, but due to the nature of the task, this was not possible.

Zone of Proximal Development

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (1979) was incorporated into the design of the unit, whereby students could be pushed to the degree they were comfortable with, in order to develop new understandings and test the boundaries of their knowledge. Students had the opportunity to include the bare minimum of information required to pass the Outcome, or go beyond to demonstrate higher order thinking skills and an extended understanding of the topic. With assistance from the teacher and myself, students were offered new ways of thinking, new ways of searching and retrieving information, in order to push their understandings further. This meant that, while many students would be quite comfortable doing the absolute bare minimum, by imbuing search strategy and other information literacy skills upon them, they felt encouraged to go beyond their comfort zone. It is the lag of the developmental process behind the learning process that defines this zone, and provides opportunities for growth and exploration (Vygotsky, 1978). Giving guidance throughout the unit helped students better develop problem solving skills and gave them the confidence to try that which seemed beyond them.

Vygotsky’s Zone of Proximal Development (etec)

‘Phases of Inquiry’ Model

The inquiry model that best suits this ILA is Kath Murdoch’s ‘Phases of Inquiry’ (2010).

Phases of Inquiry (Kath Murdoch, 2010)

Although this unit was not developed based on a particular Inquiry model, I believe Murdoch’s Inquiry Cycle best captures the elements of the information seeking process that occurred during the unit. This Inquiry Cycle reflects the general stages of the unit without requiring many of the more in depth stages that other models may use. Within a unit ruled by the Australian Curriculum and very little movement for change, Murdoch’s model is simplified, flexible and reflective of the demanding nature of secondary Outcome units.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

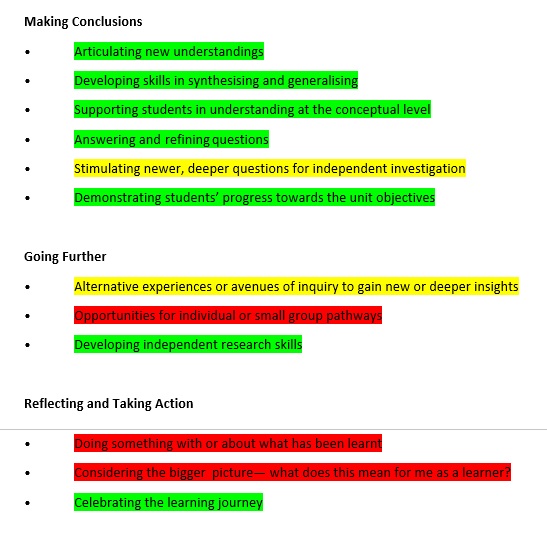

The following excerpt examines to what degree each stage of the cycle is carried out within the unit. Green sentences indicate elements done well; yellow indicates a partial completion; and red indicates that the stage was not evident.

The Inquiry Process and Thinking (Thinking Strategies for the Classroom)

—————————————————————————————————————————–

During the ‘Tuning in‘ phase, some background information was presented to the class in an introductory lesson to the unit. Students were tuned in to the topic through the teacher’s vivid descriptions of the events of the Cold War. Murdoch points out that this phase is particularly important, as it sets the scene for learning and helps kick-start the thinking process. “At the heart of the inquiry process is the task of helping deepen students’ understandings by guiding their thinking about lower level ‘facts’ through to concepts and, ulitmately, to higher level, transferable generalizations.” (Murdoch, 2010b, p. 1). This introduction and use of lower level facts gives students “thinking leverage”- while only a portion of the Cold War history has been discussed, this gives students something worth thinking about (Murdoch, 2010c). During this phase, students were given the opportunity to ask questions and gain an interest in the topic. It is also during this phase that Questionnaire 1 was carried out and students were given the opportunity to reflect upon prior knowledge and potential positives and negatives of the ISP.

This was closely followed by the ‘Finding out‘ phase. For the most part, focus questions and suggestions for potential research choices were given to the students: mainly to avoid students spending excessive time labouring on choosing research choices that may not lead to the intended outcomes or find appropriate information. It was at this stage that assistance with search strategies was provided by both the teacher and myself. Students used these new searching skills to collect information and determine its validity and accuracy.

Once students had found sufficient information, then began the ‘Sorting out‘ phase, whereby students would analyse the collected information and discard irrelevant material. Many of the students began to jot down dot points of relevant information from websites and books to help with this phase. It was also at this time that Questionnaire 2 was implemented. When it became clear that many students were struggling to find relevant material and cull down their collected materials, action was taken to work with and scaffold students that experienced difficulties, whilst working with the class as a whole. Please see the blog post ‘Action Taken’ for strategies implemented during this phase.

Students then moved on to the ‘Going further‘ phase, summarising and organising information in order to develop new understandings and make meaning. During this phase, students reflected upon their work, determining whether more information was needed, and moving back through the phases if necessary. This stage is where learning becomes far more individualised, as students take their own personal paths through Outcome questions and refine their work to reflect their knowledge and understandings. Students raise and revisit questions, extend experiences and challenge their assumptions (Murdoch, 2010). When questioned about this phase, one student replied “Now I know what topic I’m doing, I can look at things that really interest me, as well as the other things the teacher wants us to do”.

The ILA begins to draw to a close during the ‘Making conclusions‘ phase, where students formulate their assignment, ensuring that they have achieved what is required. Students come to conclusions about the specific elements of the Cold War that they have been researching. One student commented “I didn’t realise until now the bad things Russia has done to America. It was a huge power struggle, and I think it changed the way we all look at Russia from then on”.

The final phase, ‘Taking action‘, while not fully followed, at least retained some elements of evaluation and reflection on what the students had learnt. Questionnaire 3 was carried out during this time, requiring students to look back on their learning journey and reflect on new learnings, difficulties and challenges overcome.

Murdoch offers an interesting notion about inquiry learning:

“In an inquiring classroom, it is the LEARNER that constructs his/her understandings– moving from the known to the new.” (Murdoch, 2010a, p.4). Whilst the unit was not as in depth, student oriented and rich in information literacy as Khulthau may hope for in her Information Seeking Process model, it at least provides scaffolding, differentiation and questioning elements that are key components of inquiry based learning.

GeST Windows

Information literacy can be seen to fit into 3 different categories: Generic, Situated and Transformative. Lupton & Bruce (2010) have utilised these categories to develop the concept of GeST Windows. These three categories are the key paradigms through which the literacy discourse is operationalized, that view literacy as:

– A set of generic skills (bhevaioural)

– Situated in social practices (sociocultural)

– Transformative, for oneself and for society (critical)

(Lupton & Bruce, 2010)

The Nested GeST Windows (Lupton, 2010)

I believe that the ILA has demonstrated that it is situated within a combination of the Generic Window and Situated Window. Within the Generic Window, literacy is regarded as a set of skills to be learnt. “literacy is neutral, objective, text-based, apolitical, reproductive, standardized and universal” (Lupton & Bruce, 2010, p.5). Students within this ILA develop set skills such as locating information, citing work, ICT skills, information evaluation and selection, as per the Australian Curriculum standards. However, students are required to make meaning by engaging with mutliple forms of text such as recounts, videos, images and song, which is reflective of the Situated Window. Within the Situated Window, information literacy is seen as a range of contextualised information practices (Lupton & Bruce, 2010). Throughout the ILA, students are expected to locate information using purposeful search strategies and use the information to make conclusions based on the social and cultural contexts analysed. Rather than being nothing more than a generic unit that teaches skills, the Outcome tasks require students to critically engage with information and make meaning in order to form personal opinions and ideas. The ILA fails to meet the requirements of the Transformative Window, as it does not provide the opportunity to critique society, challenge the status quo or carry out a form of action in response to the task.

—————————————————————————————————————————–

Recommendations to improve the ILA include:

– Plan inquiry based units based on a specific inquiry model to ensure students practice and develop essential information literacy skills. Murdoch’s Cycle of Inquiry provides an immersive experience and the potential for transformative learning when all elements are carried out effectively. As the cycle has less stages than other inquiry models, such as Kuhlthau’s Guided Inquiry, it provides more flexibility to fit within a senior secondary History unit.

– Provide students with the opportunity to generate and answer their own questions surrounding the Cold War, rather than allowing students to choose from a select few topics. This immerses students in the learning experience and requires a greater amount of higher order and critical thinking.

– Consistent reminders to use search methods other than Google, and use of Boolean operators within search strings. This will ensure that students are exposed to a range of databases and search programs and find information that is varied and wide reaching. Examples of useful search websites include:

– Explicit teaching of evaluation of resources to determine relevancy and appropriateness to the task. Without appropriate information literacy skills, students are not equipped to determine the usefulness of information based on credibility, authority and relevance. If students are explicitly taught how to find meaningful, credible information, they are more likely to have higher quality work.

– As ICT was such a large component of the research process, students could have been provided the opportunity to present their assignment in a number of ways, such as a blog, wiki, movie, poster or oral presentation/Power Point presentation. Gardiner’s Theory of Multiple Intelligences is centred around the notion that all students are skilled at different things, and to determine that only one intelligence is valued, marginalises all others. By providing alternatives for information presentation, the ILA caters for individuals and better values the knowledge of all.

– Provide students with the opportunity to collaborate with others either on elements of the Outcome, or to engage in small group/whole class discussion. Through discussion, students can share ideas, examine issues, make sense of information and reflect on their learning experiences.

– Allow time to reflect on the learning experienced, conclusions made and discuss how the unit has changed students beliefs and understandings. This may take the form of group discussions, class discussions or personal reflective writing.

References:

Australian Curriculum, Assessment and Reporting Authority. (2013). Modern history: Curriculum content. Retrieved from http://www.australiancurriculum.edu.au/SeniorSecondary/Humanities-and-Social-Sciences/Modern-History/Curriculum/SeniorSecondary

Lupton, M., & Bruce, C. (2010). Chapter 1 : windows on information literacy worlds : generic, situated and transformative perspectives, in Lloyd, A., & Talja, S., Practicing information literacy: bringing theories of learning, practice, and information literacy together. Wagga Wagga: Centre for Information Studies, 3-37.

Murdoch, K. (2010a). The inquiring classroom: What do effective inquiry teachers do? Text slides from conference keynote address. Retrieved from <http://www.kathmurdoch.com.au/uploads/media/whatdoinquiryteachersdo.pdf>

Murdoch, K. (2010b). Inquiry learning – journeys through the thinking processes. Retrieved from <http://www.kathmurdoch.com.au/uploads/media/inquirylearning.pdf>

Murdoch, K. (2010c). An overview of the integrated inquiry planning model. Retrieved from <http://www.kathmurdoch.com.au/uploads/media/murdochmodelforinquiry2010.pdf>

Vygotsky, L. (1978). Interaction between learning and new development. Mind and Society. MA: Harvard University Press.

When students completed Questionnaire 1 after the introductory lesson, it provided an insight into the prior knowledge and understandings, apprehensions and overall feelings of the students. Upon analysing the surveys, it was clear that while the majority of students had no real knowledge of the Cold War and many were worried about staying on task and finding the right material. Upon analysing Questionnaire 2, it became evident that there were a number of students disengaged and struggling with the inquiry task. Many students indicated within the surveys that they had experienced difficulties with the skills required to complete the Outcome. These included researching, recording information and selecting information.

In order to scaffold students during their information journey, it was necessary to plan and implement a number of short lessons at the beginning of each period to work on different research skills. In particular, search strategies were a large part of my focus, demonstrating to students how easily search strings can effect results. Students quickly began to realise the merit in the clever shaping of search strings and terms such as AND, OR, NOT and ( ) became common within their searches. A discussion about the validity and accuracy of materials followed this, explicitly stating to students the need to make sure information was from a reliable source. It was during the ‘Sorting out’ stage of Murdoch’s ‘Phases of Inquiry’ that students began to realise that the propaganda they had chosen to analyse was in some cases fake and a modern recreation. This prompted us to look back again at the accuracy of information in a short lesson before class commencement.

For lower achieving students, the enormity of the task, coupled with requirements to find specific relevant materials whilst staying focussed, meant that they were struggling to make connections between the readings and understandings. Struggling students were very hesitant to be involved in teacher/librarian assistance, preferring to work alone wherever possible. This may potentially be due to looking ‘uncool’ for needing help in front of friends, or maybe because they felt unsure or lacked confidence. The teacher and I worked together to assist those that continued to struggle, working on specific information literacy skills that would help them to complete the task.

Murdoch’s (2010) ‘Phases of Inquiry’ model acknowledges the need to teach specific information literacy skills within an inquiry based learning setting. These include gathering prior knowledge; use different methodologies to find information; refine thinking; make connections; evaluate sources, synthesise information and reflect on thinking. Even though scaffolding has been used for these elements leading up to the unit and across other disciplines, it was necessary to remind students that help was available if needed and to think back to what they had learnt in the past. At this stage, locating relevant information was the most difficult skill students experienced.

For many students, their finished work and end results were a reflection of their hard work and organisation. Students that struggled to remain on task and fully utilise the time given to them found it a difficult and overwhelming unit.

References

Murdoch, K. (2010c). An overview of the integrated inquiry planning model. Retrieved from <http://www.kathmurdoch.com.au/uploads/media/murdochmodelforinquiry2010.pdf>

Question 1

The responses for Survey 1 were pleasantly surprising. The responses were mostly facts, with students often simply jotting down two word topics rather than recording what they know about each topic. As such, these were not counted as facts and were not included in the results. Students were apt to write a short fact statement, but would rarely go into depth and explain these facts in greater detail. Because of this, concluding statements were rare indeed. However, Survey 1 recorded the highest amount of conclusions between the three surveys (only 2 concluding statements were given amongst 21 students).

Survey 2 offered a greater amount of information recorded, showing 49 factual statements amongst 23 students. Explanation statements remained steady, but these tended to be solely amongst those students who had taken a proactive approach to the assignment and were naturally higher achieving. At times, where some students would go to great length to demonstrate their understandings, others would barely write a full sentence. This is surprising, given that these Year 11 students chose the subject as an elective and were there out of genuine desire to learn history. Having said that, not everybody enjoys undertaking surveys and questionnaires, and motivation to complete the surveys to a high degree differ greatly.

Survey 3 was done poorly in general. By this point, students had worked tirelessly to complete their assignments over a series of weeks and student attendance was far lower than normal on the day of submission. Whether that be due to the fact some students had not yet completed the assignment and had stayed home to finish it, it is unknown. For Survey 3, only 16 students were available to do the questionnaire. It demonstrated a dramatic drop in factual statements. Out of 16 children, 7 students answered this question either through stating topics they had learnt about without any factual statements or explanation, or by making statements such as “I know who Khruschev is and what he did”. As such, these responses were not counted towards factual statements.

Reasons for the decline in quality of responses may differ greatly. As the students were informed that the questionnaires did not affect their final assignment marks, together with it being the conclusion of the unit of work, they may have been less inclined to complete the work well. Over the course of the three surveys, I was disappointed as the results were not as I expected. I expected that the number of factual statements, explanations and conclusions would increase over time as students understandings of the topic grew. However, the results did not accurately reflect this idea. The lack of effort as the surveys progressed was in fact completely inconsistent with the quality of the students assignments. Most students successfully achieved the criteria for the outcome.

Question 2

The level of interest dropped slightly as the unit of work progressed. In Survey 1, all but one student showed great enthusiasm for the topic, but as the unit progressed, students began to feel bogged down by the responsibility of selecting their own topics within the broader concept and hence collect suitable material to complete the activity. This may have been one of the reasons for an drop in interest within Survey 2. However, as students became more immersed in the topic, it soon became clear that it was the same students each time showing the same lack of interest. By Survey 3, these same students still showed no increased interest in the unit. Survey 3 was introduced after the completion of the unit, and there were feelings of satisfaction and relief that the outcome was finally completed. There was an increase in students that already had ‘quite a bit’ of interest, to ‘a great deal’ of interest in the final survey.

Overall, it is clear that the majority of these students chose history as an elective subject in Year 11 because they already had a good amount of interest in modern history. Despite difficulties in refining search terms and locating suitable resources within the information seeking process, morale and interest continued to run high throughout the unit. The level of student choice and responsibility over their own learning would certainly have contributed to this engagement and motivation to complete the outcome to a high degree.

Question 3

The level of knowledge grew as the students progressed through the research process. Those students who perceived themselves as having no knowledge did mostly by survey 3, record that they had gained some knowledge.

The response ‘not much’ dropped considerably over the course of the unit, starting at 81% in Survey 1 and easing down to 39% and 19% by the conclusion of the unit. Those that counted themselves to still be at this level of knowledge may have felt so because of disengagement or lack of interest in the topic. Those that do not critically engage with a topic cannot hope to get the most out of the unit. Conversely, it can be seen that although only 14% of students reported having ‘quite a bit’ of knowledge of the topic, increased dramatically up to 56% in Survey 3, while there was also 25% of students now demonstrated a solid, extensive understanding of the topic. Although consistent with the end quality of the assignments, it does not match up with the quality of knowledge demonstrated in Question 1, and hence does not capture the true abilities of the class. This may be because many of the students showed an unwillingness to put effort into any of the open-ended questions within the surveys. It appears as though they do not see much potential in reflecting upon their own learning during and after the ISP process.

Question 4

This table demonstrates that 5 areas were developed within the responses.

1/ Organisational skills

2/ Engagement with the task

3/ Location of information

4/ Selection of relevant information

5/ Creation of assignment

The components in the second column represent important skills attributed to each theme. Columns 3 and 4 include examples of student survey responses that reflect some of the components.

The results for Question 4 were mostly what I expected. It was disappointing throughout all 3 surveys to see how little thought and effort students had put into the responses, often shortly stating things like ‘finding info’ or ‘read books’. At Year 11 standard, I had hoped for more. The responses did, however, give enough information to create the chart above. Throughout all 3 surveys, it is easy to see that the theme ‘Location of information’ remains the most discussed element of the ISP. Answers differed greatly depending on the time frame in which each survey was undertaken. For example, Survey 1 was implemented at the introduction of the unit of work. Students had not yet started selecting specific topics or begun locating information. Because of this, there was a greater focus on the creation of bibliographies and citations within ‘Organisational skills’. Upon reflecting on their learning in Survey 3, students noted that citations weren’t as easy as they had initially thought, nor was the ease of finding relevant materials. Some students admitted that it was far too easy to procrastinate, as they were often working loudly at tables in the library with their friends.

Interestingly, there were not many responses regarding the creation of the assignment. Rather, the collection of information seemed among the easiest to undertake. As the question directly states ‘things that are easy during the research process’, it is perhaps not surprising that students took this literally and stuck within the collection phase, rather than analysing the entire ISP.

Overall, the elements that students found to be easy throughout the ISP were fairly consistent throughout the unit. For example, ‘Location of information’ held steady as one of the biggest factors deemed as ‘easy’ by students, despite a small drop by the conclusion of the unit due to difficulties in finding unaltered, complete propaganda for use within the assignment. Responses regarding engagement were largely seen as insignificant when weighed up against other, larger factors such as location, relevancy of materials and development of the assignment. However, this factor becomes more prominent during Question 5.

Question 5

It is ironic indeed that whilst so many students found it easy to locate information when undertaking the assignment, the theme ‘Location of information’ still remains one of the top difficulties during the ISP. It seems that while finding information was hard to do, finding information relevant to the student needs, and hence understanding the jargon within the sources proved to be even more difficult. As the ISP progressed, some students found themselves struggling to refine search terms, pick out important points from resources and attempt to make meaning through the linkage of a range of sources. Searching for ‘real propaganda’ became a source of frustration and overwhelming anxiety amongst the students, as it soon became clear that the searches students were carrying out were not yielding accurate and relevant results.

Perceptions of the task being too hard, too long and boring seem to have influenced some student’s ability to engage with the inquiry. Some comments were also expressed from the students that demonstrated a dislike for the topic, frustration and negativity. Despite this, difficulties in elements of the theme ‘Engagement with task’ diminished at the conclusion of the unit, perhaps because there may have been greater challenges within the unit that made ‘focussing’ and ‘staying on task’ sit at the back of students minds.

It is interesting to note that, at the introduction of this unit, students had worries and concerns over things such as referencing, finding relevant materials and summarising. These issues diminished considerably over time, and, by Survey 3, were a shadow of what they previously were. However, the fact that 5 less students participated in Survey 3 than Survey 1, may have altered the findings somewhat. Answers provided got smaller and smaller over time, to the point where students would write a word or two, or ignore the question altogether. This may suggest that students overcame their difficulties and had nothing to report on, or sheer laziness may have prevailed.

Question 6

While student responses in Survey 3 for Question 6 were incredibly brief in general, responses fit into one of these 5 categories:

– Facts (e.g. “I learnt about the history of various countries”)

– Time management (e.g. “I learnt the importance of time management”)

– Focus (e.g. “How to focus in class”)

– Referencing (e.g. “Ways that work for me when referring to the research”)

– Search strategies (e.g. “The best way to use the Internet to find what I need”)

Overall, general motivation to complete Survey 3 was at an all time low. After working hard for a number of weeks, students wanted to complete the questionnaire as quickly as possible, without careful consideration and reflection. As expected, from the 16 students that responded, 11 responded with brief facts, reeling off the topics that they had learnt about without any in depth discussion or explanation. However, 2 students focused their reflection on their ability to manage time effectively, with 2 also commenting on their new referencing skills. Only 1 student made mention of her new ability to focus in class, and 1 took note of how her refinement in search strategies had helped her achieve her task. This question did not effectively demonstrate the real learning experiences of the students, but their assignments showed the extent of knowledge, inquiry and information skills necessary to achieve the outcomes.

Question 7a

Surprisingly, at the halfway point in the unit, it was nice to see that almost half of the students were feeling confident about their search strategies and overall progress of the assignment. However, this still meant that 52% of students were feeling dissatisfied overall. At this point during the ISP, students ranged between the stages of ‘Selection’, ‘Exploration’, ‘Formulation’ and ‘Collection’. The variance in stages was quite surprising. When asked directly to make comments about their progress, I was hard pressed to find a student that didn’t reply with ‘It’s going fine’. Students asking for help was a rare occasion. Rather, they would suffer in silence and bottle up emotions of frustration and confusion. Only when pushed would they admit that they needed help. The discrepancy between responses given in Survey 2 and interview questions were quite confusing. This may be due to peer pressure- asking for help may be seen as ‘uncool’, therefore students are less likely to do so.

Question 7b

At the conclusion of the unit, and the completion of Survey 3, students showed a 63% confidence rate. When added to the 25% ‘Happy’ rate, it meant that 88% of students felt that they were satisfied with how their information seeking process went, and the quality of their final assignment. When compared to the 48% positivity rate of Survey 2, there is a 40% jump. It seems that the 12% of students that felt they under performed were part of the same friends group and were also the ones that gave negative responses of interest and engagement in the topic, and also had problems finding and retrieving relevant information. According the response of one student, her ADHD ‘stops me doing things if I don’t have a break’. These particular students may have needed more individual work time with the teacher or myself, or worked separately from the group in order to focus.

The ILA, as previously mentioned, was SAC 1 for students studying VCE Units 1 & 2 History. The SAC was undertaken by twenty-five students at an all-girls college in South East Melbourne. As the outcomes to be achieved are predetermined by the Australian Curriculum, there was no room as a teacher-librarian to input ideas and offer suggestions when planning, as it is required to be the same SAC that all other schools complete. However, I was open to ask questions, observe and use information gathered to help students along the Information Seeking Process (Kuhlthau, 2012).

In order to support students along their learning journey, I decided that the main avenue of data collection would be through the use of Student Learning through Inquiry Measure (SLIM) Toolkit questionnaires (Todd, Kuhlthau and Heinstrom, 2005). These would be administered at the very beginning of the unit of work, midway and at the conclusion. After an introductory talk about my aims and the purpose of the data collection, Questionnaire 1 was then administered. Afterwards, students were able to begin their tasks while I collected observations of students and their research methods and information literacy skills as they progress through the ISP. At the conclusion of the first lesson, I was able to look at student answers within the questionnaire and determine their current understandings. Of particular interest to me was the attitudes students held towards the topic, and any apprehensiveness or worry they harboured. Through careful analysis of emotions and potential issues, I was able to alter my methods of instruction to suit the needs of the students.

Again, in the middle of the ISP, students undertook Questionnaire 2, which contained many similar questions to before, but now focused specifically on difficulties and achievements in the research process. The difficulties provided further fodder for change in instruction to assist with search strategies and research skills. Questionnaire 3, administered at the closing of the unit, provided a chance for students to reflect on what they learnt, evaluate the quality of their work and examine the research skills developed throughout the unit.

For a qualitative study to be considered valid, it is essential that a mixed method approach be utilised to enhance and validate the research (Creswell, 2012). Bulsara (n.d) argues that variation in data leads to greater validity and ensures there are no ‘gaps’ in the information collected. Together with this, a triangulation approach ensures that pre-existing assumptions from the researcher are less likely, and can answer the research question from a number of perspectives (Bulsara, n.d). Therefore, I decided to use conversations with students throughout the unit to further refine answers given in the questionnaires, and provide a chance for students to give responses in a less formal way. As students are far more likely to give in to peer pressure and potentially lie in questionnaires, the conversations gave a chance for students to talk without peer influence.

References:

Bulsara, C. (n.d). Using a mixed methods approach to enhance and validate your research [Lecture Notes]. Retrieved from http://www.nd.edu.au/downloads/research/ihrr/using_mixed_methods_approach_to_enhance_and_validate_your_research.pdf

Creswell, J. W. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research (3rd edition) Upper Saddle River, NJ: Merrill Prentice Hall

Kuhlthau, C. (2007). Guided inquiry: Learning in the 21st century. Libraries Unlimited.

VCE 20th Century History

Unit 2- 1945-2000

Outcome 1

Year 11 History- Three week unit of work

Girls’ Catholic College- South East Melbourne

In this study of modern history, in particular, the Cold War era, students will:

Analyse and discuss how post-war societies used ideologies to legitimise their worldview and portray competing systems.

Knowledge and understanding outcomes:

Students will:

– Use chronological sequencing to demonstrate the relationship between events and developments in different periods and places

– Use historical terms and concepts

– Identify and locate relevant sources, using ICT and other methods

– Identify the origin, purpose and context of primary and secondary sources

– Process and synthesise information from a range of sources for use as evidence in an historical argument

– Identify and analyse the perspectives of people from the past

– Develop texts, particularly descriptions and discussions that use evidence from a range of sources that are referenced

– Select and use a range of communication forms (oral, graphic, written) and digital technologies

The class teacher, in collaboration with me, the teacher librarian, guides the students to ask deep questions as they research across a number of areas, relating to the Cold War period.

Once students have completed their tasks, they present it in the form of a report.

Task 1:

Analyse and compare two propaganda items produced by the USA and the USSR during the Cold War period.

Include in your analysis:

– A description of the literal and symbolic elements of the propaganda

– The historical context in which the propaganda was used

– The ideologies expressed in the propaganda

– The target audience

– Response by the government and people to the propaganda

– What the propaganda war revealed about the Cold War conflict between the USA and the USSR

Task 2:

Create a biographical profile of two political leaders who held opposing ideological views during the Cold War.

Examples could include:

– Harry Truman and Joseph Stalin

– Castro or Khrushchev and John F Kennedy

– Mao Tse Tung and Chiang Kai Shek

– Ho Chi Minh and Ngo Dinh Diem

In your biographical profile, include primary quotations from both leaders that reflect their different ideologies.

Task 3:

Investigate a conflict that existed between the USA and the USSR during the years 1950-1975. This can include the following events:

– The Korean War 1950-1953

– The Arms Race, MAD and Nuclear Fallout

– The Space Race

– The Berlin Wall 1961

– The Bay of Pigs Invasion and the Cuban Missile Crisis 1961-1962

– The Vietnam War 1965-1975

In summation, you must include the following areas:

– The origins and background to the crisis

– A description of the crisis

– Who is involved (major figure heads)

– The USA and the USSE’s position in your chosen crisis

– The ideologies of communism vs. democracy played out in this crisis

– The outcome of the crisis

Primary and secondary sources such as maps, visuals, pictures, posters, graphs, etc. should be used to support your research.

References and Images:

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. (2013). AusVELS Curriculum- Foundation to 10 History, retrieved from http://ausvels.vcaa.vic.edu.au/The-Humanities-History/Curriculum/F-10#level=10

Cold War Propaganda and Politics, retrieved from ahersko.wordpress.com

Vintage & Modern Propaganda Posters, retrieved from www.andysowards.com

Cold War Propaganda from Behind the Iron Curtain, retrieved from www.chasingdragons.org

Did the Cold War Ever End? Retrieved from hyperallergic.com

Going through the process of changing search-strings, collecting resources and bringing it all together, I was truly unsure of how well I carried out my research, and the extent to which my journey reflected the Information Seeking Process. Reading over the stages of ISP, I could see how well some elements matched the ILA that I have been observing over the past few weeks, but I had not even thought of the fact that I, too, was carrying out my own ILA, and that there may potentially be some elements missing. Upon starting this blog, I had very little knowledge about inquiry learning and the advantages that come with it. Now, I am stupefied as to why I have never tried it within my own classroom, and angry that it was not sufficiently covered during my bachelor degree.

According to Kuhlthau, the stages of the Information Seeking Process are initiation, selection, exploration, formulation, collection, presentation and assessment. The process acknowledges the varying emotions and behaviours that can arise throughout the ISP, and Kuhlthau points out that “The constructive process is not a comfortable, smooth transition but rather an odyssey of unsettling and sometimes threatening experiences” (1994, p.58).

I find this ISP model to be particularly helpful, because of the acknowledgement that the process can be at times, overwhelming and frustrating, and that this is simply a normal aspect. I think back to the times where I have been given an assignment that has required total student responsibility and control, and the feelings of confusion and fear at the thought of being responsible for selecting a topic alone.

1. Initiation

The search process began with the announcement of the blog assignment, to which an enormous amount of apprehension and uncertainty arose. This was the very first time in 4.5 years of university that the topic of inquiry learning had become the primary focus of research. As I read carefully through the CLN650 unit guide, question after question began to be scrawled onto the sides of the paper. Why hadn’t this ever been covered before? Furthermore, why had I not ever thought to incorporate this into my classroom? What exactly am I meant to do? I felt overwhelmed at the prospect of using new technology, undertaking huge searches and creating a seemingly limitless blog. No limits? No way. I need structure and guidance and I need it now! This particular stage of observing and exploring potential was akin to the ‘Watching’ stage of the 8 W’s model (Lamb, Johnson & Smith, 1997), whereby I was but a beginner, standing at the start of endless possibility.

2. Selection

It was at this stage that I managed to organise the observation of my ILA- a Year 11 History class over the course of three weeks. Once the ILA had been organised, my direction was clear- my research process would focus on senior secondary inquiry learning within the history classroom. However, not having any knowledge of senior history beyond my own days in high school, I was concerned that my limited knowledge, together with only a budding understanding of inquiry learning and the ISP, that I would not bring to class the expertise and confidence that the history teacher herself brought with her. But, having decided upon my own topic for the research process, there was definitely, as Kuhlthau describes, a sense of elation, followed by apprehension of the task that lay ahead (2007).

3. Exploration

The exploratory process is the stage that caused the most frustration, as it became evident after attempting various searches through Google, Google Scholar, and A+ Education, that the search strings being used were not finding resources that I would deem suitable for the particular topic. The term ‘history’ used in the search strings would consistently source articles that would relate to ‘the history of… ‘. This is consistent with Kuhlthau’s description of the stage, whereby students may become frequently confused by inconsistencies and incompatibilities that are encountered (2007). “For most students, this is the most difficult stage of the research process. Students can easily become frustrated and discouraged” (Kuhlthau, 2007, p.18). Perhaps because I was so confident that the search strings I used would yield some really useful results, I felt discouraged when it was becoming evident that the process would prove more difficult than I expected.

However, after finding a few usable readings, I was able to begin creating my annotated bibliography, and further define my focus for research. It became clear that using the term ‘history’ in search strings would not yield the results I sought, so ‘SOSE’ and ‘Social studies’ became the primary focus. The skills I developed in expert searching during this phase completely changed the way I would usually go about researching a topic, honing my search skills and learning how to find information quickly and effectively. As the searches became more and more effective, so too did my annotated bibliography begin to grow and develop.

4. Formulation

In my formulation stage I used the information I had collected in my annotated bibliography to establish a clear focus for my essay. This was incredibly difficult to me, and a form of essay I had not ever attempted before. Normally, I would determine a focus, then collect information and resources pertinent to the topic. This is also termed as a ‘top-down’ approach to information organisation. Locating information, and using this as the basis to form a thesis statement- well, to me that is far more challenging a task, as you are restricted to the resources collected- classed as a ‘bottom-up’ approach to information organisation. I found myself going back and forth between ‘Webbing’ and ‘Wiggling’ (Lamb et. al, 1997)- exploring information, evaluating its usefulness, then altering searches over and over until I found what I desired. The more information I found, the deeper the understanding of my focus topic, and inquiry learning overall. By the end, I felt inspired. All of these approaches to best practice were just sitting here, and I’d not ever tried to utilise them within my classroom? I felt appalled at myself! I finally understood all the theorists when they said that inquiry learning was engaging and motivating, developing deep understanding through student participation and the construction of knowledge.

5. Collection

And so my essay began to take shape, using the collected resources to back up my central thesis statement. Kuhlthau describes the collection stage as the gathering of information that “defines, extends and supports the focus” (2007, p.20). It was at this stage I also noted that there were some gaps in my ability to create a cohesive argument within the essay, and I went back to my expert searches in an attempt to find more, in particular, resources about the scaffolding of inquiry learning and the advantages that support has towards student-centred learning. My confidence and interest in the topic grew, supporting Kuhlthau’s idea that this stage, due to the developing expertise and a budding sense of ownership, can be one of the most positive stages of the ISP (2007).

6. Presentation

The presentation stage is defined as the culmination of the inquiry process, whereby the information that has been located, gathered and analysed, comes together to form an end product (Kuhlthau, 2007). I felt an immense feeling of satisfaction after completing the essay, because it was the product of almost two months of locating, examining, and synthesising information. Kuhlthau points out that at this point of the ISP, individuals may feel disappointed that their work does not necessarily meet their expectations (2007). Despite feeling elated that the process was almost complete, I began to look back on old work and think “Gosh, is this really the best I could do?”. And, through the process of re-reading, I began to pick out points for improvement, and started thinking about ways that I could do so. In this fashion, I would go back through the 8 W’s phases in order to improve upon small things, until the blog deemed fit for Presentation (Kuhlthau, 2007) and ‘Waving’ (communicating) (Lamb et. al, 1997).

7. Assessment

Although my journey has not yet ended, I am surprised to see, despite not thinking about it along the way, that my own Information search process does indeed include many elements of Kuhlthau’s own ISP. If anything, being aware of the process throughout my learning journey has helped me to understand that, in order to maximise learning, the seven steps of ISP need to occur, and that learning can be organised into logical steps. I will continue to reflect on this and the concepts that broaden my understandings of inquiry learning as my journey continues, and I look forward to analysing my Year 11 History class ILA and comparing the learning journeys of both.

References:

Kuhlthau, C.; Maniotes, L. and Caspari, A, (2012). Chapter 1 : Guided Inquiry Design: The Process, the Learning, and the Team. In Kuhlthau, C.; Maniotes, L. and Caspari, A, Guided Inquiry design: A framework for inquiry in your school, (pp.1 – 15). Santa Barbara: Libraries Unlimited.

Lamb, A., Johnson, L., & Smith, N. (1997). Wondering, wiggling, and weaving: A new model for project and community based learning on the web. Learning and Leading with Technology, 24(7), 6-13.

Guided Inquiry in Senior Secondary History

The fast paced and ever changing nature of humanity has meant that the children of today’s society are faced with more challenges and overstimulation than ever before. It is evident that, in order to cater for individuals within education, a change in teaching pedagogy is crucial. The concept of Inquiry Learning, whereby students become active participants in the information seeking process, provides the opportunity for students to gain deeper understandings of curriculum content and information literacy concepts (FitzGerald, 2011). Through the incorporation of Guided Inquiry into integrated units of work, teachers are able to guide students through the location and selection of information, enabling them to develop the information literacy skills essential for transforming information into knowledge (Kuhlthau, 1994). Students are often presented with tasks that require them to research and utilise a range of information sources in order to make meaning and construct knowledge. Senior secondary history, and indeed, all levels of history, have been forever based on lecture and rote memorization (Wiersma, 2008), with little chance at engagement or connecting to students lives and experiences. Despite the National Curriculum and AusVELS covering Foundation to Year 10, there can be no overlooking the requirement that history must instill the capacity to “undertake historical inquiry, including skills in the analysis and use of sources, and in explanation and communication” (AusVELS, 2013). Thus, it is apparent that teachers of senior history within Victoria and nationwide should consider Guided Inquiry as a practical, meaningful and relevant approach to the curriculum, as it introduces students to tools that historians employ, requiring them to question, explore, test and argue thoughts and opinions (Fragnoli, 2008). Guided Inquiry has the potential to transform learning in the way that it: provides a scaffold to assist students in creating and constructing knowledge; lets students become active participants, responsible for their own learning; and allows essential literacy skills that are key components of 21st century learning to flourish.

Guided Inquiry allows students to become active participants in the construction of meaning. History remains a tricky subject because of its inclination to delve into research and information in a way disconnected from students lives. However, Schuster discovered through the incorporation of historical inquiry into her classroom that students were able to discover that their knowledge was indeed valued and important to their own learning, and that through the transformation of her teaching methodologies, students were equipped with skills that promoted lifelong learning (2008). FitGerald’s case study involving senior secondary history classes further cemented this argument, demonstrating that student-centred learning achieved far better success and engagement (2011). Through these case studies, it is clear that history units that incorporate Guided Inquiry give students the opportunity to construct their own understandings and become active citizens.

The Guided Inquiry process must be sufficiently scaffolded in order to support students with a team of educators who assist students in developing their information literacy skills. Dong Dong and Cher Ping (2008) posit that scaffolding instruction remains one of the key elements to the success of a historical inquiry unit, as it effectively engages and supports students throughout the information seeking process, developing skills in questioning, argumentation and analysis. This notion of scaffolding is further built on by Woelders (2007), who argues that scaffolding using Know-Wonder-Learn charts and anticipation guides creates deep critical analysis when viewing films, texts and propaganda within historical units. “Learning these critical thinking skills may also help students to develop critical-thinking habits that transfer into their leisure activities” (Woelders, 2007). Through collaboration between teachers and librarians, historical units will be able to fully utilise the skills of educators, and ensure that students are best supported during the ISP process. The Information Search Process (ISP) designed by Kuhlthau is a crucial element of Guided Inquiry, determining six stages of learning that educators can use as the basis for information literacy development (Kuhlthau, 1994). It is essential that Guided Inquiry units are developed and implemented by a team of educators who are able to guide and support students and enable them to become participatory learners and effective researchers.

Guided Inquiry allows students to work through the various stages of the ISP to develop information literacy and research skills that will enable them to become successful members of society. Gillon & Stotter (2010) believe that inquiry is a “skill for life” (p.1), creating energetic, enterprising individuals. However, they point out that within a senior secondary classroom, the rigid nature of assessment tasks makes transformation of the curriculum into a difficult task (Gillon & Stotter, 2010). It is through the combination of the skills of locating, evaluating and using, together with curriculum standards, that Guided Inquiry has the ability to encourage students to become information literature individuals, ready for the challenges of the 21st century (Kuhlthau, 1994).

Guided Inquiry is an effective method to use when developing and implementing a history unit, as it allows student to frame their own questions, forcing students to do more than just simply transport information from texts and the Internet (FitzGerald, 2011). Through utilizing specialist teachers and teacher-librarians, historical inquiry units can be built to be relevant, engaging and motivating in nature. The information seeking process and scaffolding provide the stages, opportunities and growth to develop essential information literacy skills. The numerous case studies of historical Guided Inquiry units explored demonstrate that inquiry-based learning enhances the learning experiences of students and should be considered as a productive approach to teaching history in the 21st century.

References:

Dong Dong, L. & Cher Ping, L. (2008). Scaffolding online historical inquiry tasks: a case study of two secondary school classrooms. Computers & Education, 50(4), p.1394-1410.

FitzGerald, L. (2011). The twin purposes of guided inquiry: guiding student inquiry and evidence based practice. Scan 30(1). P.26-40.

Fragnoli, K. (2006). Historical inquiry in a methods classroom: Examining our beliefs and shedding our old ways. The Social Studies 96(6). p.247

Gillon, K. & Stotter, J. (2011). Inquiry learning with senior secondary students: yes it can be done! Access, 25(3), 14-19.

Kuhlthau, Carol Collier (1994). Students and the information search process: Zones of intervention for librarians. Advances in Librarianship, 18, p. 57

Lupton, M. (2012). Inquiry skills in the Australian curriculum. Access, 26(2), 12-18.

Nayler, J. (n.d). Inquiry Approaches in Secondary Studies of Society and Environment: Key Learning Area. Retrieved 26th August 2013, http://www.qsa.qld.edu.au/3517.html

Schuster, L.A. (2008). Working-class students and historical inquiry: transforming learning in the classroom. The History Teacher, 41(2), 163-178.

Victorian Curriculum and Assessment Authority. (2013). AusVELS- History. Retrieved 29th August, 2013. http://ausvels.vcaa.vic.edu.au/The-Humanities-History/Overview/Rationale-and-Aim

Wiersma, A. (2008). A study of the teaching methods of high school history teachers. The Social Studies99(3).p. 111-116.

Woelders, A. (2007). ”It makes you think more when you watch things”: Scaffolding for historical inquiry using film in the middle school classroom. The Social Studies98(4). p.145-152.

Historical inquiry is a multifaceted phenomenon. S. G. Grant describes it as “the passion for pulling ideas apart and putting them back together” (2000, 196). According to Levstik and Barton (1997), the memorization of isolated facts rarely advances students’ conceptual understanding. Historical inquiry introduces students to the tools of historians and requires them to question, explore, test, and argue their thoughts and opinions.

After looking at Google, Google Scholar and A+ Education search databases, it is clear that my searches must be again changed to narrow the search. The topic of Science has come up often in the results, mainly because Science happens to be the subject that utilises Inquiry based learning the most.

From its basic search function, ProQuest allows us to use search terms in much the same way as Google. It allows users to nominate whether they want full text or peer reviewed articles included within the search, and is easily navigated.

Search 1. (“inquiry based” OR “guided inquiry”) AND “History” NOT science

Slowly, progress is being made. This search string aims to find any History related article linked to either inquiry learning or guided inquiry.

Analysis of Search:

This seems to have effectively blocked all the science related articles and is now focussed better on the subject of History. With 825 results, there are too many to trawl through individually, but it seems we are getting close now. The very first article is related to a case study of inquiry-based curriculum in a secondary school history class. Finally! As I look at the following documents, there are articles about interdisciplinary inquiry learning, argumentative pieces on the need to provide secondary students with thematic or inquiry based learning in order for students to work effectively in History.

The journal article, Historical Inquiry in a Methods Classroom was particularly useful, as it examines pre-service teachers and the way they utilise inquiry learning in History in relation to their pre-existing notions of social studies. It provides a glimpse into a case study of teachers and discusses how historical inquiry can be implemented within the classroom.

Search 2. (“inquiry based” OR “guided inquiry”) AND (“History” Or “Social studies”) AND “high school” NOT science

It seems that, in order to whittle down the search results so that they become more manageable, the search string inevitably becomes longer and longer. After finally trying the term ‘social studies’ and getting far more results than ‘History’, it is clear that a mixture of the two is the best method of approach. So, a search that seeks for IL or GI and History or Social studies, along with high school, but not including science topics, should bring us the ultimate search, right?

Analysis of Search:

I have to say, there are definitely more articles than I can handle (with 286 results), but being significantly narrower than Search 2, I feel that this search string is far more usable than its predecessor. Included in the search results are many articles related directly to historical inquiry- to the point where I am beginning to wonder whether ‘historical inquiry’ as a search term will bring up better search results than many of the other terms that have been used. The majority of articles are related to case studies of historical inquiry, scaffolding the teaching of inquiry based learning within the classroom, along with the use of technology within a History classroom. Overall, the most successful search yet 🙂

Search 3. “Guided Inquiry” AND “ISP”

After looking back on my successful search of this particular string through A+ Education, I decided to use the same string via ProQuest to see if it would bring anything new to the table. As A+ Education is primarily an Australian website, I hoped that ProQuest would bring out some journal articles that perhaps weren’t included within the A+ collection. I decided to further refine the search using the option to find only ‘full texts’.

Analysis of Search:

The search came back with 38 results, and immediately I saw that the emphasis of this search was on Kuhlthau’s various works. Within the first 4 results alone, three were authored by Kuhlthau. I immediately chose one of the texts for use within my annotated bibliography. While having no focus on History, the majority of the resources were still relevant to inquiry-based learning, and the knowledge therein could be easily transformed to suit that of a senior school History class. It was interesting to see that inquiry learning within a library setting was also another repeated offender.

Search 4. “Historical inquiry” AND “Social studies” AND “Secondary”

This search has been the most fruitful of all, providing many of the resources I have found and chosen for my annotated bibliography. After finding that the term ‘history‘ really was not pulling many results, I have chosen to scrap it altogether. Historical inquiry is a particular form of inquiry that is specific to the history classroom, and altered to suit the explorative nature of the subject. Therefore, I thought it more suitable than the term ‘guided inquiry‘ in this instance.

Analysis of Results:

Although the search initially produced over 900 results, I continued on a process of narrowing in order to end up with a smaller collection of resources that would be easier to deal with and navigate. Each resource related to Historical inquiry in some form or another. I especially liked how, after selecting ‘full text’, this removed the majority of the resources that could only access small portions of the text. I selected two of the possible results for use within my annotated bibliography, and was thoroughly pleased with the results.

References

Grant. S. G.. and B. A. VanSledright. 2000. Elementary social studies: Constructing a powerful approach to teaching and learning. Boston: Houghton Mifflin.

Levstik, L., and K. Barton. 1997. Doing history: Investigating with children in elementary and middle schools. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.